- Home

- Keach Hagey

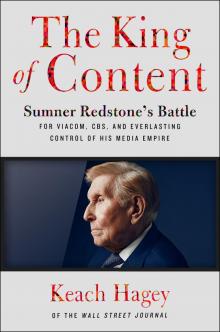

The King of Content Page 3

The King of Content Read online

Page 3

When Prohibition ended the next year, the numbers game took on an even bigger role in the underworld economy of the North and West Ends, and so did Sagansky. He became the “bank” for all of the other bookies in the neighborhoods. “Doc Sagansky put together a group of his old friends—Mickey Redstone was one of them—who chipped in to cover the bets,” said one longtime North End resident and historian. “They were a group of Jewish guys who grew up together in the West End and the other Jewish sections of Boston.” According to Gary Snyder, the grandson of Mickey’s youngest sister, Ethel, Sagansky became a key ally of the Irish Mob that controlled Boston for much of the first half of the twentieth century, through figures like four-time mayor James Michael Curley. “Sagansky was, simply put, their Jew,” Snyder said. “If Capone’s Mafia had Meyer Lansky, Boston’s Irish Mob had Harry ‘Doc Jasper’ Sagansky.”

* * *

Another of Max Rothstein’s West End neighbors was Bella Ostrovsky, the most beautiful of the four girls born to Bension and Esther Ostrovsky and the first to be born on American soil, shortly after they immigrated from Kiev at the turn of the century. In the old country, Bension had been a successful lawyer, but without a solid grasp of English, he took work in a raincoat factory, where the din from the machinery gradually deafened him. For a while, the family lived together in a rented apartment in Cambridge, but eventually Bension and Esther, a noted beauty with a fiery temperament, divorced while their youngest child, Ida, was still quite small—a highly unusual decision for Jewish families at the time. “When this was mentioned to me as a young person, it was regarded as extraordinary, maybe a little scandalous,” said Russ Charif, grandson of Rose, the Ostrovskys’ eldest child. Rose and Ida went to live with their mother, while the middle daughters, Sarah and Bella, went with their father. By the time Bella was in her late teens, they were living at 112 Poplar Street in the West End, around the corner from Max Rothstein. Blond, blue-eyed, and bright, Bella—who would later change her name to Belle as the whole family further anglicized their names—was from more modest circumstances than the Rothsteins, but she was no less ambitious. “Belle worshipped her father—how many men of that time raised two daughters alone?—and when she met her future husband, she saw a relentlessly ambitious and authoritative figure who would take care of her as well as her father had,” wrote Judith Newman, Sarah’s granddaughter, in Vanity Fair in 1999.20

In 1921, when she was eighteen or nineteen, Max and Bella Rothstein were married and began their journey toward becoming Mickey and Belle Redstone. (Max was called “Mickey” from childhood, as his mother’s accent made “Maxie” sound like Mickey, family members say.) That journey began humbly enough, with a move a few doors down the street to the Charlesbank Homes.

In his autobiography, Sumner recalls the apartment having no toilet. Richard Hartnett, a West End Museum board member who grew up in the Charlesbank Homes two decades after Sumner lived there, said the larger apartments did have bathrooms inside. “We had steam heat with janitor service. We had five rooms and we were paying $18 a month. It was great.” Children played on the rooftop, amid the hanging laundry, or at a nearby playground designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. The Rothsteins didn’t stay in the tenement for long. Family members say that during Prohibition, Morris Rohtstein’s fleet of flour and sugar company trucks were put to more lucrative use ferrying liquor from Canada to various points throughout the Northeast. And thus Mickey, the bakery “chauffeur,” joined a singular fraternity of young men from the immigrant ghettos of America’s large cities who came of age just as Prohibition was extending them a truly once-in-a-lifetime business opportunity.

Bootlegging in Boston was controlled by Charles “King” Solomon, a portly, thick-lipped crime boss whom the feds called the “Capone of the East.”21 The son of Russian Jews, Solomon had begun with the drug and lottery rackets before creating what customs officials dubbed “the wealthiest liquor syndicate ever built up in New England.”22 He became a member of the “Big Seven” bootlegging syndicate and attended the 1929 Atlantic City conference to divvy up territory alongside Meyer Lansky, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Frank Costello, Frank Erickson, Bugsy Siegel, Dutch Schultz, Abner “Longy” Zwillman, Al Capone, Waxey Gordon, and Enoch “Nucky” Thompson. By the time he was gunned down in a nightclub men’s room in 1933, he was under federal indictment for running a vast rum-running operation that allegedly brought in ships of booze from Canada and Europe and guided them up the East Coast by secret radio frequencies. After his death, the business was taken over by his lieutenants Joseph Linsey, Hyman Abrams, and Louis Fox.23

Fox, who was arrested in 1921 for the “illegal transport of liquor,” was a longtime business partner of Mickey and Sagansky’s. So, too, was Linsey, a convicted bootlegger identified by federal agents as the New England chief of a consortium that bought Canadian liquor from Seagram founder Samuel Bronfman and distributed it in the United States, alongside Lansky and Al Capone associate Joseph Fusco.24 After repeal, Linsey—like another famous Bostonian with whom he is often associated, Joseph Kennedy—went into the legitimate liquor distribution business, becoming president of Whitehall Company, distributors of Schenley liquors. Linsey’s business partnerships with Mickey stretched from the liquor business to drive-ins to dog racing. Linsey would not be bought out of his business interest with Mickey until the early 1980s, when Mickey’s son Sumner cleaned house in preparation for a run at the upper reaches of American legitimate business.

Just how deep Mickey got into bootlegging, and whether his partnership with Sagansky led him there, is unknown. But there were some hints that this street-smart kid was willing to break the law—and adept at talking his way out of a jam. At age nineteen, in the same year he would end up marrying Bella, he was arrested and held for questioning over a missing bag owned by Boston’s boxing commissioner, Carl Barrett, which contained his wife’s $700 fur neckpiece and a 250-year-old empty jewel case from France. A man in the counting room in a local newspaper office had seen a woman walking past with the fur on her shoulder, and when officers asked her about it, she said it was a present to her sister from Max Rothstein. Max told the police that he had bought the fur for $40, and apparently, that was the end of it.25

What is clear is how porous the boundaries were between legal and illegal, enterprise and racket, in the interbellum Boston in which Mickey began his working life. The dominant political figure of the era, James Michael Curley—four-time mayor, two-time congressman, and one-disastrous-time governor—served part of his last mayoral term from prison. His predecessor in the mayor’s office, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, founder of the Kennedy political dynasty and grandfather of John F. Kennedy, dealt with his own allegations of graft and corruption during his administration and remained a power broker for decades. Mickey learned early how to navigate the city’s Irish-dominated power structure. He bought a used truck, opened his own trucking firm, and, according to Newman, secured a carting contract from the city of Boston with the help of friends like “Honey Fitz.”26 His granddaughter Shari’s earliest memory of him was driving and singing old Irish songs.

He also began to invest in real estate very early, with help from his own entrepreneur father. At twenty-three, he got a bank loan to buy a $2,000 investment property in Brighton, a heavily Irish neighborhood of ample Victorians and lush yards.27 Years later, his wife, then called Belle, wrote her younger son, Eddie, amid a family dispute, holding up the loan for the property as evidence that Morris had been stingier with his children than Mickey was with his. “I remember when Sumner was a little boy Dad needed $1500,” Belle wrote. “He asked his father for a loan. His father arranged for a bank to make the loan and Dad signed a note [which] his father endorsed and he paid it back ‘with interest.’ He evidently wanted to be different with his children!!”28 But the loan was a crucially important mechanism for Mickey to build credit beyond the underground economy. Just two years later, he moved his young family to Brighton, to a roomy, four-bedroom clapboard h

ouse with a yard at 5 Bothwell Road.

By this point, in 1930, with Prohibition still going strong, Mickey was formally listing his occupation as a floor covering proprietor.29 This is how his son Sumner first remembers him. “My father peddled linoleum and I have a clear picture of him in my mind toting a huge roll over his shoulder and carrying it out to the truck,” Sumner wrote in his autobiography. Then, more dubiously: “With the money he brought in, he supported not only my mother, me and my younger brother, Edward, but his own parents and my mother’s family as well.”30

There’s little evidence to suggest this is true. Morris and Rebecca were wealthy enough to have a live-in maid, several property holdings, an eldest son who was in line to take over their business, and, by 1933, a comfortable Victorian in fashionable Brookline. But if Mickey really was supporting his parents in the final years of Prohibition, it is unlikely that he did so from linoleum alone. Family members believe that linoleum was a side business to the bootlegging and other vice rackets. By the end of the decade, Boston had four thousand speakeasies—four times the number of licensed bars in the entire state in 1918—and fifteen thousand people involved in selling illegal booze.31 When the bonanza suddenly ground to a halt with repeal in 1933, Mickey found a perfect next business: liquor wholesaling. And that business would lead Sagansky and him into a whole other aspect of the entertainment industry.

Chapter 2

The Conga Belt

Few Boston businesses flourished more under Prohibition or struggled more with its repeal than Club Mayfair, a fashionable nightclub at the edge of the theater district in Boston’s gas-lamp-lit and brick-sidewalked Bay Village neighborhood. The club had an impeccable nightlife pedigree, founded as the Renard Mayfair Club by Jacques Renard, a classically trained violinist–turned–jazz band leader who had previously cofounded the Renard Cocoanut Grove up the street in 1927. The Cocoanut Grove, resplendently kitschy with fake palm trees, rattan-covered walls, and zebra-patterned chairs, would go on to be “Boston’s number one glitter spot and the axis around which Boston’s night life revolved,” the Record American put it a few years later.

But during Prohibition, Renard forbade the Cocoanut Grove to serve alcohol, and business suffered—particularly after the stock market crash of 1929. The local underworld was not impressed. Renard’s daughter recalled to journalist Stephanie Schorow how some of them expressed their desire to see alcohol introduced. “They took my mother for a proverbial ride. Put her in the backseat of a Roadster and covered her up with a blanket and took her for a ride to Revere beach. She said there were machine guns under the sheet with her.”

Renard and his partner, master of ceremonies Mickey Alpert, couldn’t take it. They sold the club for a mere $10,000 to Charles “King” Solomon, who in 1931 donned a tuxedo and attempted to remake himself an elegant nightclub impresario. On his last night on earth, he was entertaining two young dancers at the Cocoanut Grove before heading to another nightclub, where he was shot to death, uttering the final words, “Those dirty rats got me.”1

Renard, meanwhile, went up the street and opened the smaller Mayfair to compete with the Cocoanut Grove. After another change of ownership, the club began to do well selling illegal liquor, according to the Boston Globe:2

With a membership reported to run in the thousands, lack of interference, and backed by popular fancy, the club prospered until, in the final days of prohibition, Gov. Ely told Police Commissioner Hultman to raid all suspected speakeasies. With police officers stationed inside and outside, the Mayfair finally posted a sign: “Closed for alterations.” It has not opened since.

In the wake of repeal,3 it was sold and reopened as a restaurant, and later a nightclub struggling with the decline of vaudeville. Then, suddenly, on January 29, 1940, the Boston Globe ran a large photo of a dashing man in a smart suit accented by a crisp pocket handkerchief, smiling confidently and shaking hands with a bandleader beneath the headline “New Owner-Manager of Mayfair.”4 The photo didn’t lie: it was Max Rothstein’s face, but the name, for the first time publicly, was Michael Redstone.

* * *

The name change was a common maneuver for Jewish immigrant families, even in the best of times, and these were not the best of times.

Germany had just invaded Poland the previous September, and the Nazis were forcing all of Poland’s Jews to wear identifying badges. In the United States, where the increasingly anti-Semitic radio broadcasts of Charles Coughlin had been drawing tens of millions of listeners throughout the last decade, a 1939 Roper poll found that just 39 percent of Americans felt Jews should be treated like everyone else, while 51 percent were somewhere on a spectrum of belief ranging from wanting Jews not to mingle socially to wanting them deported. Within this group, 31 percent agreed that “Jews have somewhat different business methods and therefore some measures should be taken to prevent Jews from getting too much power in the business world.”5

“They felt a less conspicuously Jewish name would be helpful from a business perspective,” said Russ Charif. One close family associate said Mickey had been in line to buy the Friendly’s ice cream chain, “but when they found out he was a Jew, they refused to sell it to him.” (A spokeswoman for Friendly’s, founded in Massachusetts in 1935 by brothers S. Prestley and Curtis Blake, said, “Since the brothers are now 100 and 103, they don’t really recall this.”)

Moreover, given the particularly colorful history of Boston’s nightlife district, known as the Conga Belt, “it was also to avoid confusion with Arnold Rothstein, who was accused of fixing the World Series,” Charif said. Rothstein, who was shot over gambling debts in 1928, was the leader of New York’s Jewish mob and the first to run his gambling and bootlegging rackets like a corporation. In an ironic twist, the mobster used the pseudonym Redstone Stable for his racehorses—“red stone” is a literal translation of the German name Rothstein—and his character in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire uses the alias “Redstone” for his banking transactions.6

Sumner makes a similar argument in his autobiography, but some who know the family say his real concerns were about Rothsteins closer to home. His cousin Irving Rothstein—the son of Mickey’s big brother Jake—was a longtime figure in the gambling rackets in Boston,7 having married the sister of Burton “Chico” Krantz; Krantz became famous late in life when he became a key witness in the case against Whitey Bulger. Another cousin, Edward Rothstein—the son of Mickey’s uncle Barney—was also wrapped up enough in the bootlegging, gambling, and loan-sharking rackets to wind up stuffed in the trunk of a car in 1960 with five bullets in the back of his head.8

Sumner, who had been bar mitzvahed and grew up attending temple on holidays, described the name change as an idea of his father’s that he accepted only reluctantly. “Redstone sounded so solidly American, so ecumenical, so Christian,” Sumner wrote in his autobiography. “I thought my father was trying to walk away from our being Jewish.” But people close to the family say it was more his idea than his father’s. “Sumner was going into a clean field and didn’t want to be involved with that,” said one family associate.

Regardless whose idea it was, the Rothsteins became the Redstones just as both father and son were in the midst of social transformation. Sumner had always been exceptionally clever, and his mother had resorted to any means necessary—including lying down on the floor and faking a guilt-inducing heart attack—to ensure that he devoted his every waking moment to study. A few months after Mickey took over the Mayfair, Mickey and Belle sat in the wood-paneled auditorium of the prestigious Boston Latin School and beamed as they watched their firstborn walk to the podium again and again, scooping up nearly every award that the country’s oldest school had to bestow on its graduating seniors. The modern prize. The classics prize. The Benjamin Franklin Award for being first in his class. A scholarship to Harvard University, to which his academic record granted him admission without even having to take the college boards.9

Sumner entered Harvard College the next fall as “Sumner Mu

rray Redstone.”

* * *

Mickey, meanwhile, was also entering a new echelon of society. The Sunrise had been a success, and he and Doc Sagansky were looking to expand their partnership to new ventures.10 By the late 1930s, Club Mayfair was owned by Benny Gaines, who was booking vaudeville circuit regulars like Belle Baker, the singer famed for “My Yiddishe Mama,” and the singing comedy duo Cross and Dunn. But vaudeville was dying, and Gaines was having trouble making a go of it.11 Mickey told the Boston Globe’s nightlife columnist, Joseph Dinneen, a few years later that he took the Mayfair as a “gift” in 1939 and stepped out of the wholesale liquor business to run it. “A discouraged owner handed him the night club lock, stock and barrel and said: ‘When, as and if you make any money there you can pay me for it,’” Dinneen wrote. “Mickey has made considerable money there and has paid for the club.”12

Just how he paid for it was always a matter of some mystery. It would come out in court a few years later that Mickey borrowed $10,000 from Sagansky to buy the club in 1941, and the corporation he set up to own the Mayfair would borrow another $11,000 from Sagansky over the next two years, paying him back with $3,000 interest.13 “Mickey came along and told my dad about the nightclub, and because they were successful with the drive-in together, they invested in the two nightclubs,” Sagansky’s son Bob Sage said. “They had been partners ever since.”

The King of Content

The King of Content